Melancholie Ästhetik der Vergänglichkeit und Leere – Eine Sammlungsschau

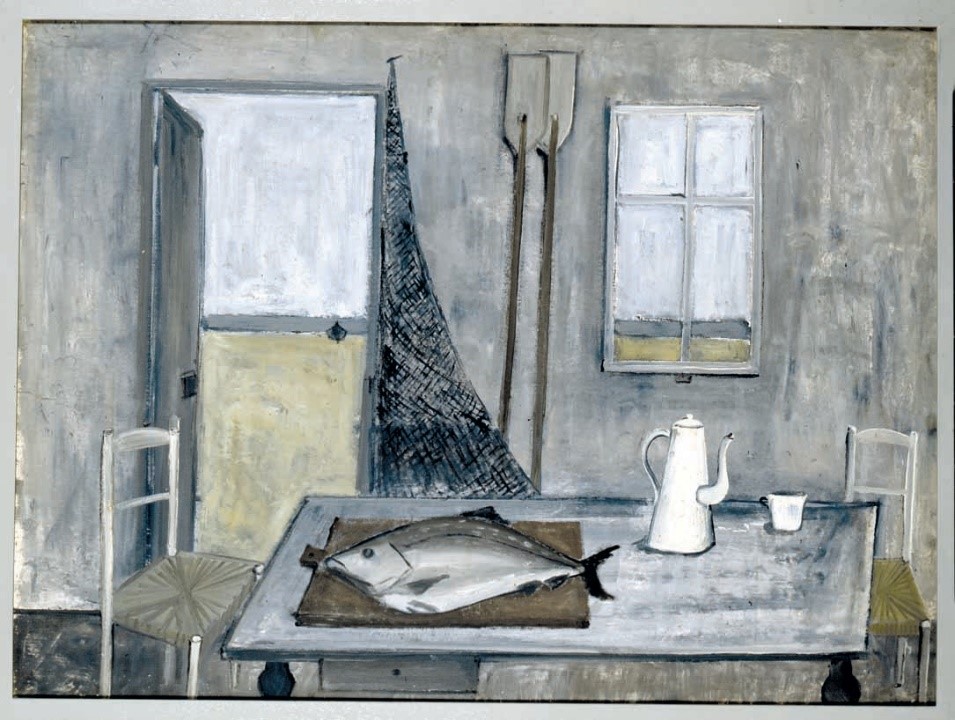

Ernst Schroeder, Fischerhütte auf Usedom, 1956, Öl auf Pappe © Nachlass Ernst Schroeder, Foto: BLMK

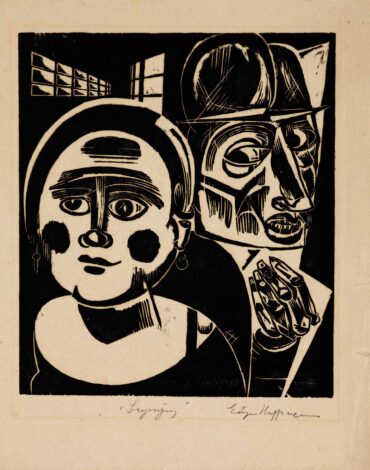

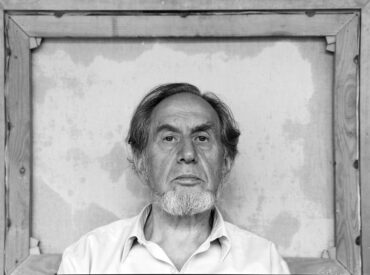

Falko Behrendt, Manfred Butzmann, Christa Böhme, Lothar Böhme, Manfred Böttcher, Fritz Cremer, Albert Ebert, Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Clemens Gröszer, Lea Grundig, Eberhard Göschel, Gussy Hippold-Ahnert, Eugen Hoffmann, Manfred Kastner, Klaus Kehrwald, Konrad Knebel, Herbert Kunze, Claudia Kutžera, Erich Lindenberg, Harald Metzkes, Otto Niemeyer-Holstein, Uwe Pfeifer, Núria Quevedo, Theodor Rosenhauer, Wilhelm Rudolph, Ernst Schroeder, Rosemarie Schulze, Frank Seidel, Max Uhlig, Trak Wendisch

Anders als in vormodernen Gesellschaften wird der Mensch heutzutage nicht mehr in geschlossene Welterklärungssysteme hineingeboren. Die Freiheit des Menschen zwingt ihn, selbst nach Identität und Lebenssinn zu suchen. Dabei kann der empfundene Mangel an authentischer Einheit zwischen Individuum und Welt eine schmerzhafte Nachdenklichkeit auslösen, die gemeinhin als Melancholie bekannt ist. Spätestens seit der Frühromantik ist diese Bruchlinie immer wieder Ausgangspunkt philosophischer und ästhetischer Überlegungen geworden.

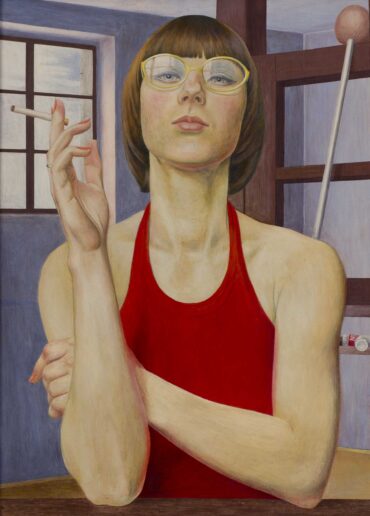

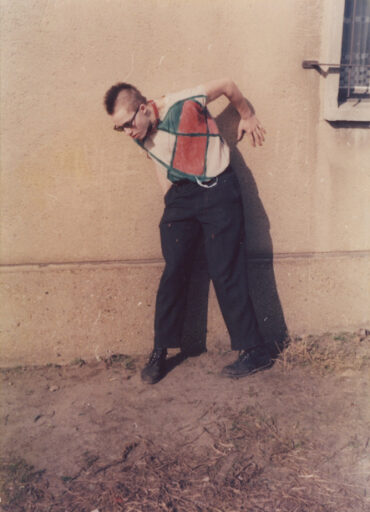

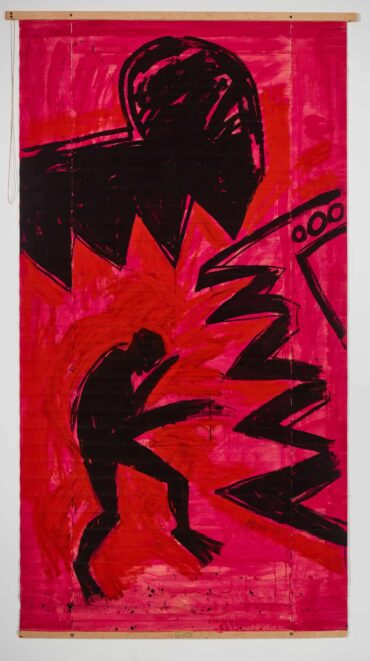

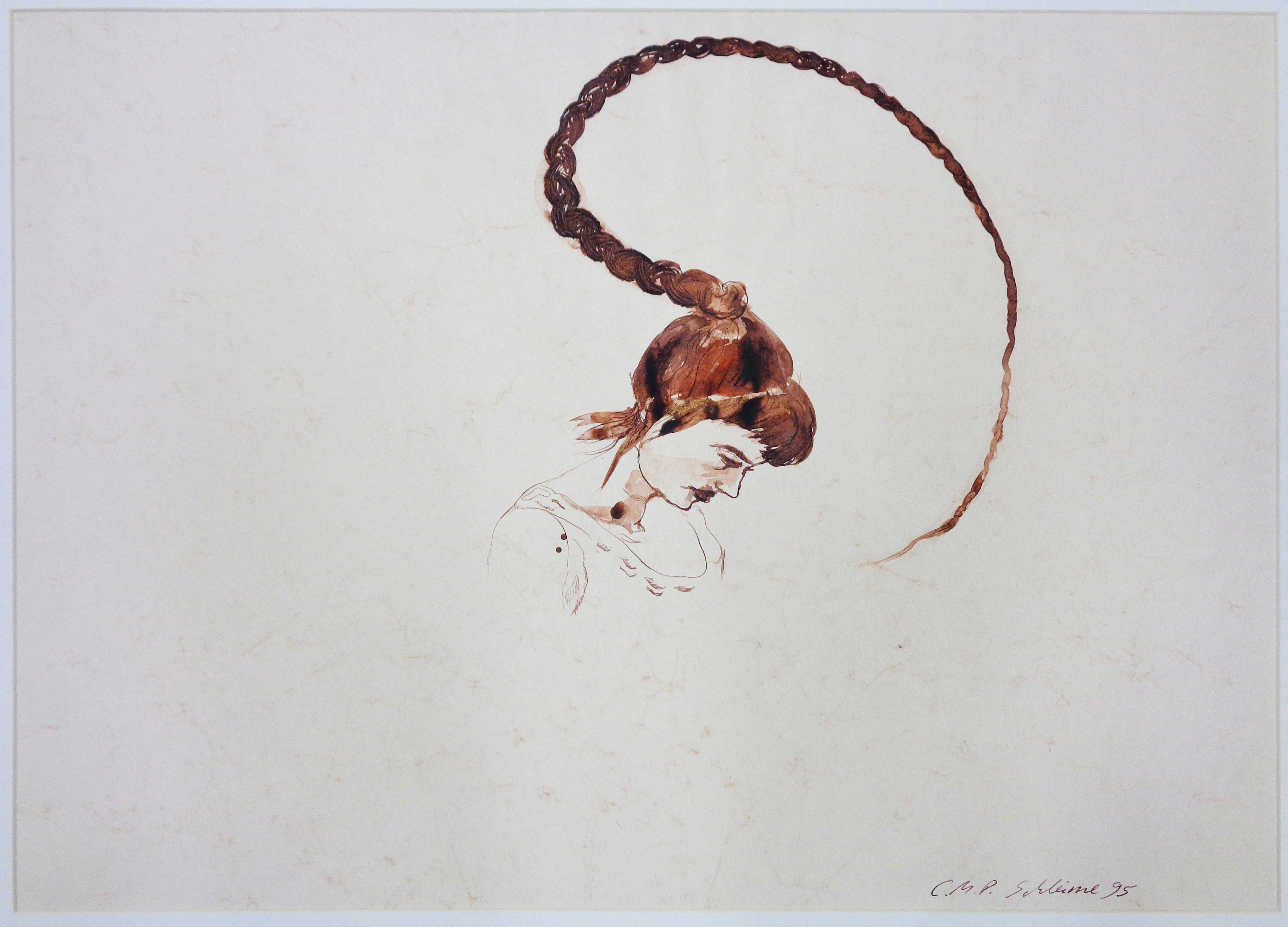

Die Ausstellung zeigt Werke aus der Sammlung Grafik und Malerei des BLMK, die den Blick in genau diese düsteren Sphären des modernen Seelenlebens richten. Wichtige Aspekte sind dabei die Flüchtigkeit der Momente und Erscheinungen oder die Tristesse des Alltags. Genauso werden aber auch Entfremdungsgefühle zwischen dem Individuum und seinen Mitmenschen, der Natur oder seiner städtischen Umgebung künstlerisch verarbeitet. Dabei erzeugt der melancholische Blick ein komplexes Spannungsfeld, das sich zwischen Gegensätzen wie Einsamkeit und Freiheit, Verfall und Erneuerung oder auch Optimismus und Pessimismus bewegt.

…

Unlike in pre-modern societies, people today are no longer born into closed systems of explaining the world. People’s freedom forces them to search for their own identity and meaning in life. The perceived lack of authentic unity between the individual and the world can trigger a painful thoughtfulness, commonly known as melancholy. Since early Romanticism at the latest, this fault line has repeatedly become the starting point for philosophical and aesthetic considerations.

The exhibition shows works from the BLMK’s graphic and painting collection, which direct our gaze into precisely these dark spheres of modern mental life. Important aspects are the fleetingness of moments and phenomena or the dreariness of everyday life. In the same way, feelings of alienation between the individual and his fellow human beings, nature or his urban environment are also processed artistically. The melancholic view creates a complex field of tension that moves between opposites such as loneliness and freedom, decay and renewal or even optimism and pessimism.